Who’ll win in November?

It’s anyone’s guess.

That means it’s important to consider outcomes from either possible outcome.

Last week, Freeport Society friend and Chief Research Officer at TradeSmith Justice Litle riffed on some of the risks posed by an incoming Trump administration. As Justice explained it, an attempt to “fix” the trade deficit too quickly via high tariffs creates the very real possibility of a debt and currency crisis.

That is something we’re always on high alert for here at The Freeport Society. So, owning “anti-dollars” is a no-brainer… even in more normal times… and these are not normal times.

But what about an incoming Harris administration?

What new risks do we need to watch out for in the event that Vice President Kamala Harris pulls off a win in November?

Justice is back today with his thoughts on that.

An incoming Harris administration, he says, could bring back some of the worst aspects of 1970s malaise.

In a word, stagflation.

How could it unfold… and how can you prepare?

Read on to find out. Over to you, Justice!

To life, liberty, and the pursuit of wealth,

Charles Sizemore

Chief Investment Strategist, The Freeport Society

What Would a Harris Administration’s Policy Goals Look Like?

By Justice Litle, Chief Research Officer, TradeSmith

“I have always depended on the kindness of strangers,” says Blanche DuBois in the final scene of A Streetcar Named Desire.

The United States depends on the kindness of strangers with respect to financing the national debt.

It is a relationship that has built up over decades. The U.S. buys cheap, imported goods paid for with dollars… the dollars get parked in U.S. Treasuries as a function of surplus country savings… the world’s willingness to buy and hold roughly $8 trillion worth of U.S. Treasuries helps keep demand strong and long-term interest rates low.

However, this relationship is problematic to the extent it hurts American industry.

If American consumers are buying cheap imports, they aren’t buying goods made in the United States.

It’s a vendor-finance relationship where, as the rich customer, the United States holds the power. If the U.S. walks away, the vendor — i.e., the surplus country providing the financing by holding U.S. Treasuries — loses a major source of revenue.

But for the United States, the cost of the existing relationship is a weaker domestic market because American producers are competing with cheap imported goods paid for on credit, supplied in the form of surplus countries buying U.S. Treasuries with the dollars they receive. And the cost of ending the relationship is losing access to that financing arrangement (no more $8 trillion of Treasuries in foreign reserve accounts).

As we have explained, an incoming Trump administration would seek to end this imbalance.

From a Trump-Vance point of view, the greatest macroeconomic evil is the U.S. trade deficit, which represents the large gap between how much stuff Americans are buying from the world versus how much stuff the U.S. is selling to the world in return.

We have described the Trump administration’s plans and policies as likely to trigger a U.S. sovereign-debt crisis because the vendor-finance relationship has two sides. One side is the aforementioned trade deficit. The other side is the willingness of surplus countries to hold $8 trillion in U.S. Treasuries (the finance part of the vendor-finance setup).

Attempting to shrink the trade deficit quickly and aggressively — by, say, imposing 10% global tariffs and 60% tariffs on China — would be like going cold turkey on a drug addiction. It would not just be trade flows that come to a sudden stop, but the incentive for surplus countries to buy and hold large volumes of U.S. Treasuries.

We argue that a U.S. sovereign-debt crisis would be the outcome of trying to end this multi-decade relationship too quickly.

Goldman Sachs says the outcome is so volatile they can’t even model it.

That is the major worry for an incoming Trump administration. The potential fallout from upending the global order — severing trade flows that have been entrenched since the early 2000s — could be economically catastrophic.

But what about an incoming Harris administration?

What reason for concern might their policies bring?

Stagflation and a Multiyear Bear Market

In brief, a Harris administration could bring about stagflation and a multiyear bear market — and they could do so on purpose.

Not literally on purpose in the sense of saying, “Our goal is to have persistent inflation and a tepid economy as stock prices fall,” but in the sense that the priorities of a Harris administration could well bring about those results: a stagflationary environment with a deteriorating outlook for stocks.

Why might that be the case?

In simple terms, a Harris administration would seek to transfer income out of the hands of shareholders and into the hands of workers. The overall goal, if not stated out loud, would be to have profit margins shrink so that labor compensation can rise.

As a thought experiment, take California’s recent wage hike for fast-food workers.

As of April 1, 2024, the minimum wage for more than half a million California fast-food workers was raised to $20 per hour, a roughly $5 increase.

Fast-food franchise owners complained bitterly about this. Worker hours were cut and locations were shut down in the aftermath of the wage hike.

But how does one measure whether the policy was successful or not?

From the eyes of the California State Legislature, a successful outcome might look something like this: Five years from now, the consumption of fast food in California is the same, but the fast-food business is less profitable for franchisees because workers are getting a larger share of the same pie.

The $20 minimum wage might be considered a failure, on the other hand, if five years from now the California fast-food industry has been crippled, making the revenue pie smaller… leaving fewer workers earning less aggregate income overall.

Note in either case, though, that making franchisees less profitable — reducing the profits of being an owner in the fast-food business — is not a measure of success from the California State Legislature. If those owners grumble and complain about how the business is nowhere near as profitable as it used to be, but they stay in business and adjust to paying their workers more, that is a win in the legislature’s eyes.

From a shareholder point of view, the goal of a business is to maximize profit share. If a company has $25 in profits on $100 in revenue, that is excellent. If that same company has just $10 in profits on $100 in revenue, that is nowhere near as good.

But from a worker point of view, maximizing the share of revenue that goes to workers is more important than maximizing profits. Workers might prefer the outcome where a company has $10 in profits on $100 in revenue, as opposed to $25 in profits, if the other $15 is allocated to higher wages.

What we are describing here is a permanent tension between capital and labor, where shareholders (stock market investors) are on the side of capital. The more profit that accrues to shareholders, the less compensation there is for workers. The more benefits and pay that accrue to workers, the less profit there is for shareholders.

A Harris administration will have progressive policies in the sense of siding with employees. It will seek to transfer capital away from shareholders and into the pockets of workers, not just through wage increases but also legislative changes that mandate larger benefits for workers and the expansion of pro-worker policies in areas like healthcare and childcare.

A Harris administration would also raise taxes — and taxes on the wealthy, in particular.

In an effort to pay for policy expansion, and to prevent the federal budget deficit from exploding beyond $2 trillion, a Harris administration might also seek to institute a wealth tax.

A wealth tax would probably function like a property tax for illiquid capital assets. Homeowners in most states are used to paying a property tax assessed against the value of their home each year. A wealth tax would be assessed against the value of unrealized capital gains on illiquid assets above a certain threshold… say $100 million.

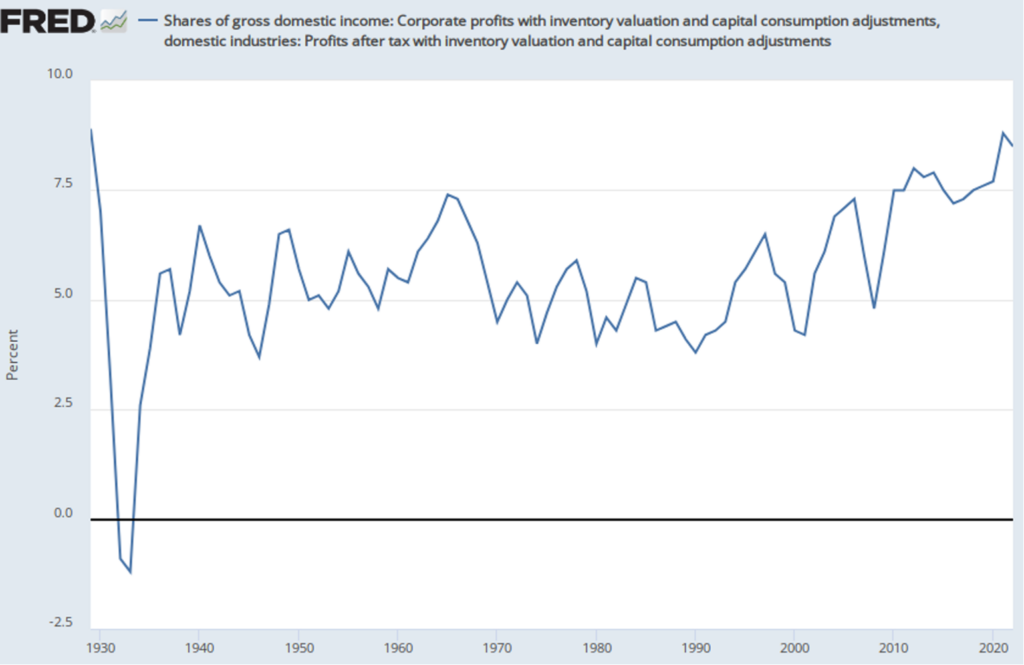

In terms of measuring policy success, a Harris administration might consider a metric like corporate profits as a percentage of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP).

Currently, corporate profits as a percentage of GDP are at their highest level in 95 years. They were only barely higher in 1929.

Shareholders like the current state of affairs. Fat profit margins translate to higher corporate earnings, which then translate to higher equity valuations.

As a Harris administration policy goal, reducing corporate profits as a percentage of GDP would be a proxy for taking some of that profit away from shareholders and allocating it back to workers.

An incoming Harris administration might also focus on this policy stat: From 1979 until today, the inflation-adjusted median real earnings of U.S. workers aged 16 and older has increased by less than 10%.

U.S. worker earnings power at the right tail of the bell curve has gone up far more than that, but the median reflects the data point in the middle of the curve — the halfway mark between high and low.

From a pro-worker perspective, this less-than-10% increase in inflation-adjusted median worker earnings since 1979 is far too small in comparison to corporate profit margins that have more than doubled (from 4% of GDP in 1980 to 8.5% today).

Anything Else?

A Harris administration would not be as likely to cause a U.S. sovereign-debt crisis for two simple reasons:

- It would be less willing to upend the global order, which would mean a greater degree of policy continuity on trade.

- It would seek to aggressively raise taxes to pay for new programs and rein in the budget deficit.

The challenge for investors, and the U.S. economy, is this: A simultaneous focus on raising taxes and reducing corporate profit margins (for the purpose of transferring gain from shareholders back to workers) would hammer the stock market.

If corporate profit margins shrink because wage costs are going up (think $20 fast-food workers in California), even as the cost of government-mandated benefit programs are going up, earnings-per-share outlooks will weaken.

At the same time, transferring capital from shareholders to workers, and from higher-income households to lower-income households, is inherently inflationary because it increases consumer spending at the margins.

This has to do with the propensity to save versus the propensity to spend: Wealthy households are more likely to save additional income whereas less-wealthy households are more likely to spend it.

If, say, a top 10% income household has an extra $100 in monthly income, it likely ends up in some type of retirement vehicle or savings account.

If a bottom 50% household receives that $100, on the other hand, it will more likely go toward purchasing goods or services that were previously out of reach.

Then, too, under a Harris administration, higher tax revenues would likely be used to offset the cost of new policy programs more so than to close the fiscal budget deficit.

That means worries of long-term interest rates creeping higher (as opposed to spiking wildly in the midst of crisis) would persist in tandem with persistent inflation pressures borne of high levels of government spending and mandated income transfers via wage agreements and benefits.

In short, this is a case of “pick your poison” with either incoming administration, be it Republican or Democrat. The policy choices will be wildly different, but the core set of issues is the same.

The inevitability of poison comes, in part, from a debt-and-deficits situation that has steadily grown worse over the past two decades — from the early 2000s onward, when surplus countries started aggressively buying U.S. Treasuries to kickstart a mercantilist vendor-finance relationship — coupled with today’s liquidity-powered equity market extremes that echo 1929.

These factors imply a built-in economic reckoning that has been delayed, but not denied, regardless of who wins the White House.

The question is not whether the reckoning shows up, but how it will go.

Until next time,

Justice Litle

Chief Research Officer, TradeSmith